Thinking (Generously) Through Non-Binary Visibility and Attending to Difference

Oct 21, 2019

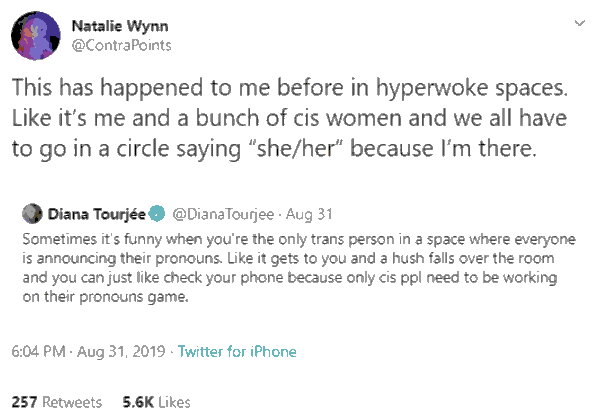

Over the past few months, I have witnessed a pretty sharp increase in conversations surrounding the visibility of non-binary folks. Much of this has stemmed from controversy surrounding Natalie Wynn the creator of ContraPoints and her comments regarding they/them pronouns. A lot has been said and written about the comments that started the controversy, I am not going to unpack the whole thing here but you can check the endnotes of this post for links to some of those discussions. Instead, I would like to focus in on one of the comments that started this whole thing:

She followed this up with the following:

“I guess it’s good for people who use they/them pronouns only and want only gender neutral language. But it comes at the minor expense of semi-passable transes like me and that’s super fucking hard for us.”

Again, I am not going to unpack this whole thing but I would like to dig into what I think is a common thread between this controversy and the controversy that surrounded Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie in 2017 when comments she made were seen as transphobic. The common thread being that in both cases, these women were attempting to attend to the nuances of embodied experience in relation to gender identity. Were they successful? Probably not and I won’t be arguing or unpacking the quality of their arguments here. Instead, what I would like to do is take some time to think through the obviously contentious issue of parsing out differences between the lived experiences of different gender identities. I am going to do that mostly by focusing on the issue of visibility.

International Transgender Day of Visibility is on March 31st every year and when it roles around, I always feel conflicted because I don’t see being more visible as route to greater freedoms or more safety. Instead, I think of Michel Foucault’s discussion of the Panopticon and the recent book Trap Door. In both cases, visibility is explored not as a site of liberation but as a trap. It is through this lens that I relate to Wynn’s and Tourjée’s comments, not as a reduction of they/them identities but as a shared experience of this odd inversion where, the very spaces that claim to provide safety become the spaces where you feel most outed.

This can be especially painful for folks who have been out as trans and working on these issues long before the “Transgender Tipping Point” of 2014. For those of us who started transitioning before the media hype, we have watched as visibility went from a means of liberation to the source of violence against us: as we became more "visible" we became less safe and our right's more imperiled. Add to this the following concerns:

- - “Passing” as a certain gender (not going to get into the complexity of passing either).

- - Not wanting to be read as trans.

- - Wanting to be read as trans.

- - Non-binary folks who struggle to be seen and acknowledged.

- - Non-binary as a new site of the culture war.

- - Folks using she/her or he/him not wanting to be labeled as binary.

- - And so on.

What you are left with is a huge mess of overlapping and interrelated experiences where visibility is seen by some as their best option for representation and by others as the primary means by which they are discriminated against. Thinking of these comments through the lens of visibility, I read them not as a way of saying they/them pronouns are bad/invalid and more as a way of saying:

“I feel myself being made hyper-visible in this moment.”

So if we can start to wrestle with what it might mean for one group’s admission into a space by way of being made visible, resulting in another group feeling expelled from that same space, then maybe we can start to ask the right questions on how to better coexist in these spaces. How might we negotiate various needs for (in)visibility?

Before starting the next section of this work I want to share a portion of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s response to the controversy mentioned above:

“Because we can oppose violence against trans women while also acknowledging differences. Because we should be able to acknowledge differences while also being supportive. Because we do not have to insist, in the name of being supportive, that everything is the same. Because we run the risk of reducing gender to a single, essentialist thing.”

Attending to difference (and especially differences in embodied experience) is, in my view, a critically important component of trans studies which seems to be ever more difficult to approach (especially in “woke” spaces).

Continuing on this thread of visibility, I think there is another related complication/difference that informs the subtext of these recent arguments. That is, the privilege of passing, not in terms of passing as a certain gender, but in terms of passing as not transgender.

In this, I think of my experiences in medical spaces and in governmental spaces. In these contexts, I don’t have the option (dysphoria inducing as it would no doubt be) to not be read transgender due to the medical interventions and document modifications I have undertaken as part of my transition. To be clear before I go on, this does not make me more or less valid as a trans person, nor am I saying that non-binary people don’t have medical transitions or that all “binary” trans folks always have medical transitions. I also do not believe in trans gatekeeping. Additionally, when I speak about people passing as not trans or hiding their identity, I realize this can come at extreme emotional/mental costs and I don’t want to minimize that fact. With that said, there is a huge difference in lived experience for those of us who don’t have the privilege of opting out of transness for our safety, and it is one that often gets overlooked. To paraphrase from a friend and fellow transgender person in academia who uses “binary” pronouns:

“When I am in with my colleagues who identify as non-binary, we all proceed as if our experience is the same when I know that it’s not.”

When we reduce the experience of all trans people into a single category, these differences are often lost. Too often, the longer standing traumas of trans folks are subsumed by the “newest” frontiers of debate/conversation (newest here is in quotes because while I know non-binary gender is not actually new, in mainstream conversations it is often regarded as such). Instead of focusing on issues pertinent to many trans folks, so many conversations are instead filled with performative gestures of allyship/wokeness and policed for perceived transgressions instead of engaging with the work presented.

I think we need to figure out new ways of writing and talking about these differences so that we can engage in more nuanced conversations from the level of academia on down to Twitter comments. We need to learn how to both write in ways that don’t totalize/generalize experiences and read with a more forgiving mindset. If we do, maybe we can hang with the difficult and recurring issues raised by trans folks. All of this brings to mind something one of my graduate school professor’s Finn Enke challenged our class to do, it went something like this:

“It’s actually really easy intellectually to tear work down that you don’t like, but much harder to read work generously and try to build from it.”

So what might it mean to step back and try to read generously both a Twitter mob’s concerns and the comments that incited the mob to begin with? To read generously the work of someone in your community whose views you don’t agree with?

What I am not calling for here is entertaining the perspectives of those who don’t want trans people to have rights or who don’t think trans identities are valid. This isn’t an Ellen DeGeneres call to love the people that hate you.

Rather, I am trying to imagine a world where toxic phrases like “truscum” and “gendertrender” don’t exist (if you don’t know what these are Google it, I tried to find some concise links to add to the endnotes but couldn’t find anything I felt comfortable linking to). A world where speaking of one’s discomfort with pronoun sharing does equal non-binary discrimination, where articulating one’s experience with the medical system isn’t taken as transmedicalist, where using non-binary pronouns isn’t seen as an attack on other trans identities, and on and on and on.

Basically, a world where trans folks don’t destroy each other, an Engagement Culture to deal with differences within our community to replace our Cancel Culture.

EndNotes:

ContraPoints Controversy:

https://www.splicetoday.com/politics-and-media/the-contrapoints-twitter-debacle-explained

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Controversy:

Trap Door:

https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/trap-door

Binary:

What the fuck does “binary” mean anyway? I use she/her pronouns and wouldn’t describe my gender identity as binary but non-binary as now become largely synonymous with using they/them pronouns. This leaves trans folks who use she/her and he/him pronouns to be viewed as “binary” by default which isn’t necessarily the case for all trans folks and definitely doesn't reflect my understanding of my gender identity.

For more information or to share your thoughts about this piece, please feel free to contact me at:

[email protected]